Liberty is a word too often thrown about in voice and advertised in modern media to draw the attention of the young and the youthful-minded, who are magnetised to such concise pronouncements of social and civil freedom, and most will equate liberty with equality, which is an association of relative meaning interpreted differently by thinkers on the subject.

Liberty is a word too often thrown about in voice and advertised in modern media to draw the attention of the young and the youthful-minded, who are magnetised to such concise pronouncements of social and civil freedom, and most will equate liberty with equality, which is an association of relative meaning interpreted differently by thinkers on the subject.We all perceive liberty in one way or another; media and literature, especially, convey the concept in various formulas that are recognisable as either simple or complex. In advertising we see liberty as the right for anyone to amount to something in society, regardless of race. Education is all-inclusive, with the chance offered to the masses to learn and options to succeed given. Some books and theses have challenged old world rule on liberty and changed the public consciousness, thanks to their authors.

These people who could tell right from wrong without any coaxing and made paramount the goals of identifying, revealing and campaigning for the accountability of powers to bring justice to the concept are many. Mary Wollstonecraft, John Stuart Mills and John Wilkes are the current focus of the HCJ course. All three of them expounded on the nature of liberty and contemplated its history, currency and optimistic prosperity. For now I will focus on Wollstonecraft.

Mary Wollstonecraft (1759-1797) was a renowned feminist, whose work was later used by suffragettes in their battle for participation in the franchise that men had historically benefited from. In her early years she was an example of female humility, subjected to domestic turmoil by her drunkard father, forced by circumstances to work in different fields before becoming an accomplished female author. Of those books of hers published, A Vindication of the Rights of Woman was her most famous work.

Cardinal ideas that corresponded with her social perspective and primary objectives of her work consisted of demanding that women should receive universal education, should see the hackneyed expectations of beauty and order in middle-class women aborted and the dismissal of the entrenched condemnation of woman's intellectual equality with man. She envisaged 'autonomous beings' and an 'education for independence'.

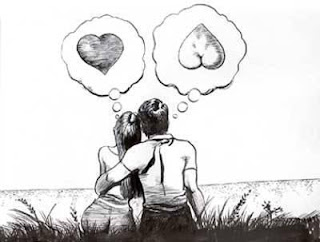

Cardinal ideas that corresponded with her social perspective and primary objectives of her work consisted of demanding that women should receive universal education, should see the hackneyed expectations of beauty and order in middle-class women aborted and the dismissal of the entrenched condemnation of woman's intellectual equality with man. She envisaged 'autonomous beings' and an 'education for independence'.Wollstonecraft's stance on the responsibility of women, comparatively greater than that of men, to change the stigma that women were only created for man's pleasure (a belief postulated by Rousseau) is unusual for a feminist - we must remember she was pre-feminine culture. Her criticism of the submission of women to derogatory 'sensibilities', as she called them, is the focal point of many passages; she claims women are marketed as 'sexual characters' and says, "Miserable, indeed, must be that being whose cultivation of mind has only tended to inflame its passions!" Nevertheless, she does contrarily admit that "from the constitution of their bodies, men seem to be designed by Providence to attain a greater degree of virtue".

Being an empiricist and advocate of education, this quote from her is archetypal: "The exercise of understanding, as life advances, is the only method pointed out by nature to calm the passions". Her feelings towards Rousseau's passions are made clear by her willingness to stamp out gender-stereotyping; Rousseau's Emile is criticised heavily by Wollstonecraft for its character Sophia, who represents women as "passive and weak". Wollstonecraft herself was a radical woman, who ventured to France during the throes of The Terror of the French Revolution.

Although her religious background makes scant appearances, leading to the conclusion she had less of an interest in theology, she does often affect to use God as a cornerstone for definition of the equality women and men share, saying that He devised that both should exist as mutual entities, not rivals for the love of God: "women were destined by Providence to acquire human virtues, and by the exercise of their understanding, that stability of character which is the firmest ground to rest our future hopes on". When she mentions "dispensations of Providence" she is alluding to the forgoing of good judgement by men, who are intended to do well by women, not oppress them.

Although her religious background makes scant appearances, leading to the conclusion she had less of an interest in theology, she does often affect to use God as a cornerstone for definition of the equality women and men share, saying that He devised that both should exist as mutual entities, not rivals for the love of God: "women were destined by Providence to acquire human virtues, and by the exercise of their understanding, that stability of character which is the firmest ground to rest our future hopes on". When she mentions "dispensations of Providence" she is alluding to the forgoing of good judgement by men, who are intended to do well by women, not oppress them.Her aforementioned dissatisfaction with Rousseau's deductions on the character of women are of interest when understanding her motives. In the first chapter, The Rights and Involved Duties of Mankind Considered, she accounts for degrees of "reason, virtue and knowledge"; she then suggests that prejudices in society go against reason which is conducive to equality among the sexes. The main prejudice she refutes is that which Rousseau imbibes and implores to be trusted: "that woman is made specially to please man". This isn't the only subject on which the two disagree. Wollstonecraft also dispels Rousseau's belief that the State of Nature was God's sole intention when he created man; she declares that the accusation that society is amoral is false as the knowledge of evil naturally leads to the virtue of good, through reason. The following quote runs through the same liberal vein:

"Firmly persuaded that no evil exists in the world that God did not design to take place, I build my belief on the perfection of God".

All in all, what Wollstonecraft wanted most was for matters of prejudice and negative discrimination to be brought to fair social justice: "Rousseau exerts himself to prove that all was right originally: a crowd of authors that all is now right: and I, that all will be right". In a prophetic sense, she predicts the rise of female action against these male-engendered evils. For her it was abysmal that women should be fooled into believing that men, in perpetuity, should love them for more than just sexual 'toys'.

Wollstonecraft's progressive empiricist nature stands firm when she admonishes Rousseau for ignoring the primary causation of social evils, as he "threw away the wheat with the chaff" when confronting "artificial manners and virtues" (he much preferred unchecked passions, what Hobbes and Locke despised). Despite a fascination with his egalitarian poise, she couldn't allow for his misconstruction of human nature.

Wollstonecraft's progressive empiricist nature stands firm when she admonishes Rousseau for ignoring the primary causation of social evils, as he "threw away the wheat with the chaff" when confronting "artificial manners and virtues" (he much preferred unchecked passions, what Hobbes and Locke despised). Despite a fascination with his egalitarian poise, she couldn't allow for his misconstruction of human nature.Wollstonecraft, like most modern day feminists, is generally forgetful, though, of her class position in society. As a pure-bred middle-class woman, she never had to face much of the degradation and poverty of her lower class sisters. But this was something she was aware of, albeit vaguely. She says at one point that "true pleasure is the reward of labour", no doubt deploring the ease with which those of the aristocracy and those more submissive women of her class enjoy the wealth of reward.

Supererogation - performance beyond call of duty - was uncommon for her kind. In describing the disparity between rich and poor, she highlights that one has the security and sensibility, but knows not how to value such stability and comfort; whereas the other understands the rewards of hard labour but continues to be deprived of what comes naturally to the discontented other. She is therefore extrapolating that both classes of women are morally and materially discontented.

She certainly was a distinguished woman, a woman who would prefer to be known as an honourable human in a world of equal human beings. But Wollstonecraft, like other valiant women such as Iris Chang, who I wrote about previously, was a martyr for her cause. After evidence of her personal affairs with men and her mental state were made public, she was downgraded in her sphere of influence as an author and her legacy overturned for a century, until it was revived by the early feminist movements of the 20th Century.

What I find most appalling about the way in which Wollstonecraft was treated publicly is how, after William Godwin's Memoirs of the Author of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman was published and interpreted, people harried her for behaving antithetically to the doctrines of her work, when we are all guilty for slipping into hypocrisy. And, not only that, but the perception of women that persists today which labels one of scandalous behaviour a whore or slag is made even more preposterous by the fact that a man who engages in the same is lauded as a hero of masculinity and a stud - this IS the ultimate hypocrisy of the sexes.

Women and men, men and women - both, as Wollstonecraft would have it, are equal, and women are entitled to the liberty that men have had the privilege of possessing since the dawn of civilisation. And, going back to my previous statement that liberty and equality aren't necessarily one and the same, both may be made to be equal in the eyes of God, but one unfortunately may have more liberty than the other. Take a guess which one.

I have a feeling this may come in very handy when it comes to revision. Good work man!

ReplyDeletehttp://jakeolivergable.blogspot.com